Some Reflections on Tiga Dara’s Restoration

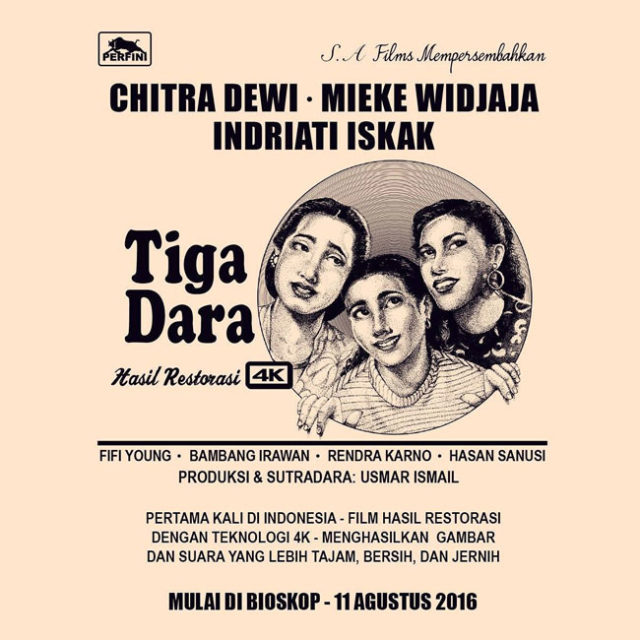

Tiga Dara promotion poster. Source: Rolingstone.co.id

Undeniable fact is the rise of Netflix and many other commercial mobile-based screening platforms allows us to experience World Cinema at large. One, for example, can see Netflix-produced series House of Cards and jump to otherwise obscure Hitchcock’s Lifeboat (1944). One can switch freely from contemporary Sundance staples to the French classics produced under German occupation during Word War II. In the very line of thought, one can imagine a similar platform designed specifically for Indonesian films; it shows variety of genres of local contents, but once you search Kafedo, Usmar Ismail’s first film from 1949, the only thing occurs on screen is zero entry. Go to Netflix and you’ll see the past of American cinema and their European counterparts. Go to local variation of Netflix (if any) and the past seems just like … Oh wait, is the year 1999 heralded by Petualangan Sherina already a distant past for most of us?

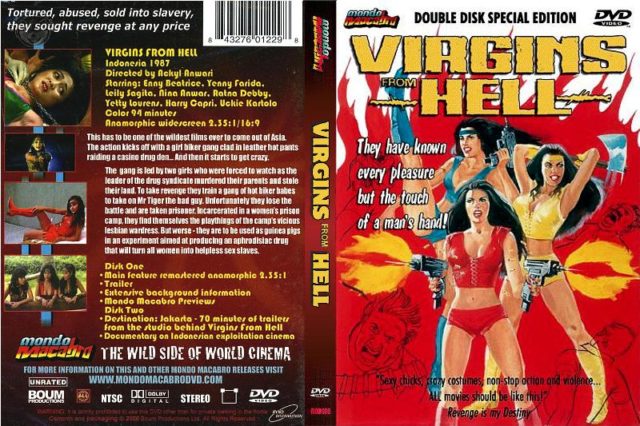

Aside the celebrated free flows of information allowed by high-speed internet, classics from Hollywood, France, or Scandinavian countries—whose status as a cinematic superpower in the beginning of 20th century seems forgotten—have long been accessible offline as different sectors in society (both state and private) invest on film archiving. There is a niche market for classics as well, either arthouse or B-movie variations. Criterion, to take one example, has been famous for releasing landmark films, often with luxury packaging and booklets. On another note, while being forgotten by many, some Indonesian horrors and action classics found are distributed by overseas DVD label, for example Pengabdi Setan (Satan’s Slave, 1982) by US-based Brentwood Home Video, Perawan Di Sarang Sindikat (Virgins from Hell, 1987) by Mondo Macabro, or Petualangan Cinta Nyi Blorong (1986) by a Japanese label. Some of these films found their second lives in locally-produced VCDs and youtube channel, albeit their lamentable condition due to its original transfer from VHS.

Mondo Macabro’s DVD release of Perawan Di Sarang Sindikat. Source

Many films produced in countries such as the United States or Denmark have been lost or beyond repair. Theodor Dreyer’s Passion of Jeanne d’Arc (1922), for instance, once mysteriously dissipated. Theaters had for years relied on re-edited versions of the same film until the master copy was discovered in a mental asylum in Norway and quickly restored in 1981. Having lost a film and found it is one thing. But preserving what is found, or even what is still intact, is another. Had a lost Indonesian film made in early 1920s been found, it might not have the same privilege with its Danish counterpart, since the Sinematek (Indonesian cinematheque), the only public repository for films in Indonesia, barely has the means to support the preservation work. Many of the celluloid suffer from untreatable physical diseases while receiving only a regular, first-aid-kit chemical treatment.

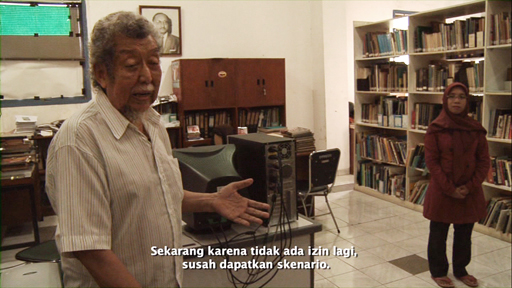

In 2013, Forum Lenteng released Anak Sabiran, Di Balik Cahaya Gemerlapan (Sang Arsip), a documentary on Misbach Yusra Biran, a filmmaker and the founder of Sinematek. The latter part of the film is a torture gallery showing the heartbreaking condition of Misbach’s noble initiative, its library, and its film vault, due to the lack of financial support. J.B. Kristanto, senior film critic and journalist has in the film expressed his concern about the Sinematek. He says that while the individuals and institutions willing to fund the Sinematek, “they have been unable to do so since it’s managing foundation has itself rejected such initiatives.”

Scene from Anak Sabiran. source: The Jakarta Post

The lack of properly watchable Indonesian classics in both offline and online platforms suggest the fact that a lot of cultural memories stored in public archives are a subject of imminent disappearance. One simply cannot write history of cinema of one’s own country without archive. And in the present times, it seems that history of a nation will not be complete without a history of its own cinema.

****

It is in this regard that the restoration of Tiga Dara (Three Ladies, 1957) spares us a moment of reflection. After about 17 months of removing mold, stiching, and scanning, the Indonesia’s early romantic comedy will now hit the theatres. Set in the ‘50s Jakarta, a classic story of three daughters looking for potential partners seems to be able to resonate to many audiences. Chitra Dewi, Mieke Wijaya, Indriati Iskak, Fifi Young, and Rendra Karno appear as the main cast. According to The Jakarta Post, the Piala Citra-winning film survived for for eight weeks straight in theaters after its initial release.

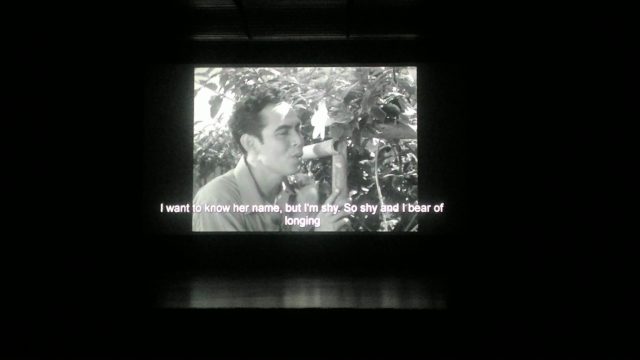

Tiga Dara’s limited screening at Institut Français d’Indonésie, July 18, 2016

However, Tiga Dara is not the first Indonesian film to be restored. 2012 saw the release of restored Lewat Djam Malam (Usmar Ismail, 1955) and in the following year, the hi-res version of Darah dan Doa (another work by Ismail, 1950) was screened in Bioskop Misbar, a festive screening event held annually in National Monument. While the restoration of Lewat djam Malam was followed by a massive campaign, the latter film had somehow made low-key public appearance.

Tiga Dara is the first Usmar’s films not dealing with war an revolution to be restored, as well as the first Asian film to be restored in 4K resolution—the second one will be Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai. Whether or not the public will respond to the film well remains to be seen in the coming months.

The restoration of Tiga Dara was initially planned by Amsterdam’s Eye Museum, says Yoki soufyan from SA Films during the limited screening of the film, July 18. Yet, it was cancelled due to the 2008 economic meltdown until a few years ago when SA Films, a local company, decided to take over the project.

It took around $220,000 to restore Tiga Dara. Sponsored by SA Films, the physical work was done in Bologne’s L’immagine Ritrovatta, involving two Indonesian nationals, Lintang Gitomartoyo and Lisabona Rahman. The digital transfer of 150,000 frame was further done in Jakarta-based Render Digital. L’immagine Ritrovatta, one of the few restoration lab, is well-known for being the only studio able to deal with a tropical mold normally found in celluloid from tropical lands. The same studio had also previously restored Lewat Djam Malam.

****

Restoration is one of the few methods of preserving films into accessible medium. Digitization, not as complex as restoration, seems to be more regular and simple. It may not involve arcane skill of removing vinegar syndrome or printing thousands of photographic frames onto cans of celluloid. However, speaking of of procedure, the reality is not as simple as in theory.

A normal transfer of celluloid material to home videos requires a specific tool called telecine. Yet, since telecine is such an expensive machine hardly affordable by the Sinematek, there appears one vernacular term for such transfer in the archive, namely Teleding, or Telecine Dinding (wall-projected telecine). This make-shift device works by video-recording a 16 or 35 mm celluloid projected onto a wall. The result is deplorable for two reasons. First, the original material are mostly corrupt and suffering from mold, and secondly, the process doesn’t do justice to the original copy; it makes use of 3:4 video resolution to record 16:9 screen. This explains why the right- and the left-end of every Indonesian classics disappear from screen when shown on national televisions.

For years Sinematek relies heavily on such poor mechanism to digitally store their collections. Digital transfer to DVD (or VCD) is also available by request for about Rp200,000 a copy (around 2009). The need for digitization of classics has actually seen a gleam of light in 2013, when the Ministry of Culture and Education launched a Rp3 billion program to digitize 29 classics. On the other hand, how the films manage to be publicly available or unavailable is another thing. Out of the 29 titles, however, only one had so far screened publicly, i.e. Bachtiar Siagian’s Violetta (1962).

There may be issues regarding copyrights entitlement, distribution rights, and screening rights that prevent the films from public availability. In fact, it has been said by some sources that it was copyrights-related dispute that had made Lewat Djam Malam and Darah dan Doa still inaccessible, despite the restoration. In fact, the copyright-related dispute is not a problem unique to Indonesian cinema. For years, Michaelangelo Antonioni’s The Passenger (1975) remained out of print until early 2000s. The film could only be circulated (in restored version) again in 2006, roughly a year prior to Antonioni’s death, since its main cast, Jack Nicholson, kept the distribution right. Thus, it remains to be seen whether or not Tiga Dara suffer from the same dispute—hopefully not. Another problem to solve is the repository. A simple question: where will the Tiga Dara’s restored copy be stored?

Windu W. Jusuf