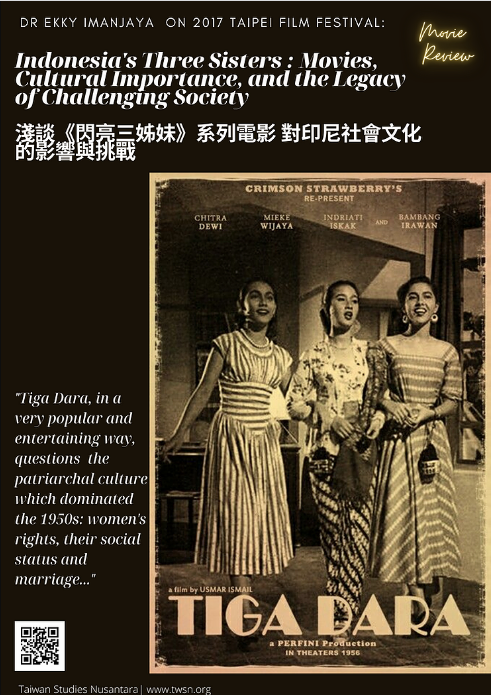

Indonesia’s Three Sisters : Movies, Cultural Importance, and the Legacy of Challenging Society

In 2016, two important Indonesian films were publicly circulated. They are interconnected and have almost the same title: Tiga Dara (Three Sisters, Usmar Ismail, 1956) was re-released in August that year and Ini Kisah Tiga Dara(Three Sassy Sisters, Nia Dinata, 2016) was circulated a month later. Both films have their own cultural importance for their respective times but they share a similar spirit of challenging society through the issues of women’s social status in Indonesia, particularly marriage culture and the question of finding husbands.

It is worth noting that, in particular cultures in Indonesia, a woman should marry by a certain age. If she is still single after “the deadline”, let’s say after 30, she will get social pressure to get married as soon as possible, or get badly stereotyped for being single. Surely, as time has passed, such perspectives would change as social values also constantly change. By watching both films, audiences can compare and contrast how society has developed and the difference between generations now further separated, namely between the conservative/old-fashioned generation and the liberal/permissive one.

Below, I will elaborate why both films are important as social archives in the Indonesian context. And hopefully non-Indonesian audiences can reflect and produce their own meanings towards the films with their own cultural values and perspectives.

Tiga Dara: Cultural Importance

Tiga Dara was recently fully restored and publicly screened in cinemas in Indonesia. Although it is not the first film to get full restoration–that would be Usmar Ismail’s Lewat Djam Malam (After Curfew, 1954), which was also screened at 2012 Cannes Classic–but Tiga Dara is the first Indonesian film to get a 4K restoration.

As with After Curfew, Tiga Dara was restored by L’Immagine Ritrovata, in Bologna, Italy. It took around $220,000 to restore the film, sponsored by SA Films from Indonesia. Two Indonesian citizens, Lintang Gitomartoyo and Lisabona Rahman, were involved in this process. The Lab was chosen because it is the only studio able to deal with a tropical mold normally found in celluloid from tropical areas, known as vinegar syndrome. This process took 8 months.

After the restoration, PT Render Digital Indonesia converted the 35mm into 4K digital. The film has 150 thousands frames and each frame took 2 hours to be converted into 4K digital format at 53 Gigabytes. In total, there are 12 Terabyte files and it took around 6 months to complete the digital conversion.

Actually, in 2011, the film was in the process of being restored by the EYE Museum Amsterdam, almost at the same time as After Curfew, but it was abandoned due to the economic crisis of the home country. Finally, SA Films took over the process.

The film was theatrically and domestically released in August 2016 and got around 30 thousand spectators in 8 weeks. Soon, the movie will be released on DVD and Blu-ray.

Tiga Dara was chosen to be fully restored in 4K because it is considered as one of the most important cultural inheritances, both as a text and for its context.

First of all, Tiga Dara, in a very popular and entertaining way, questions the patriarchal culture which dominated the 1950s. The director Usmar Ismail, known as the Father of Indonesian Cinema, critically raises issues regarding women’s rights, their social status and marriage. In the movie, there are some aspects reflecting the bad stereotype of unmarried young women as well as their roles in domestic sectors. It is important to note that the film was originally produced, distributed, and exhibited nationwide only 12 years after Indonesia’s independence, when the number of illiterate citizens dominated the nation. Later, the idea of feminism and progressive women would occur in a few of Usmar Ismail’s later films, particularly in Ananda (1970), his last movie.

These kinds of issues are still relevant even in the millennial era, and still echo in some recent Indonesian films, including Ini Kisah Tiga Dara.

Of course, Ismail also used great songs, involving the best composers and singers and that led to the timeless and jazzily ear-catching soundtrack. Big names such as Sjaiful Bachrie, Ismail Marzuki, Sam Saimun, and Bing Slamet were part of the soundtrack and music scoring team. In the 1957 Indonesian Film Festival, the film received the Citra Award—Indonesia’s equivalent of an Oscar—for Best Music.

Related to its historical importance, Tiga Dara was a trendsetter for the 1950s. It was a box office film, which premiered at Capitol Theater and screened for eight weeks in a row in prestigious movie-theatres normally associated with A-class Hollywood and other imported movies. At that time, it was very rare for an Indonesian movie to be screened in the A-class movie-theatres. In addition, President Soekarno, an American cinema fan, asked the producer to screen the film at the Presidential Palace for the private birthday party of Hartini, his beloved wife. In society, the film was one of the most discussed films of the 1950s. The social and soft drinks to batik clothing companies.

In addition, the film was imported to Malaysia, Italy (including 1959 Venice Film Festival), Yugoslavia, New Guinea, and Suriname.

We can also think of the film as a “time machine.” Through it, we can have access to and understand the zeitgeist of Jakarta and Bandung in the mid 1950s, and we can also see the development of the capital city (particularly the Cilincing picnic scene), its social life and its social problems during that era.

The Legacy of Tiga Dara

The resonance of Tiga Dara is strong, even in today’s film culture. There are at least two films from the 1980s which were influenced by it, namely Tiga Dara Mencari Cinta (Three Girls Finding Love, Djun Saptohadi, 1980) and Pacar Ketinggalan Kereta (Lover Left by the Train, Teguh Karya, 1989).

For a more recent case, we have Three Sassy Sisters. In September 2016, a month after the re-release of Tiga Dara, Ini Kisah Tiga Dara was theatrically released. The female director Nia Dinata remembers that she watched Tiga Dara on TVRI (the only TV station at the time). It was one of the first Indonesian musical films she had seen. As a director and producer who constantly makes films about women’s rights and equality (such as Berbagi Suami/Love For Share, 2006, and Perempuan Punya Cerita/Chants of Lotus, 2007), she was interested in making a similar film. However, Nia Dinata explains that Ini Kisah Tiga Dara is not a remake of Tiga Dara, even though it is “inspired by” the classical film.

However, her film has many similarities to the classic one. The basic plot and story is similar, depicting three sisters being raised by a grandmother and a single father. They face the problems of the marriage culture and women’s rights, as well as sibling rivalries towards a man. The focus of the main storyline is also the grandma who does many things to patiently “force” her eldest granddaughter to marry as soon as possible, and then many problems develop from that situation. It is also a musical, and it includes Tiga Dara’s theme song. In fact, the Indonesian title comes from a line from in the Tiga Dara theme song.

At the same time, there are some differences. Dinata, with Lucky Kuswandi, wrote the script in 2016, within a different context and social problems, and with more modern and contemporary approaches. Unlike the classic film, in this movie the three sisters have jobs (a chef, a PR and marketing manager, and a voluntary teacher for children) in their dad’s boutique hotel at the seaside resort of Maumere. The tension between feminism, patriarchy and matriarchy inevitably become more visible than in the classic film.

Since the two films are situated in different time periods with different problems, Dinata put new songs in the movie as a way in which she could communicate and express new voices. And, the whole spirit of the story was embodied in a song titled Matriarch. The new songs and arrangements were done by music directors, Aghi Narottama and Bemby Gusti and, unlike the classic film, sung by the original cast.

The strong, aggressive main characters (particularly the youngest sister) has led the Indonesian censorship board to classify the film as an adult movie (only for adults 21 years and above). Discourses on female empowerment even more prominently occur in this film.

The other different elements are the location and color format. The classic film is in black and white and located in Jakarta and Bandung. The modern version benefits from exploring the colorful culture and landscape of Maumere and Flores Island to support the director’s statement. So, the film invites us to take a journey to exotic places such as Geliting traditional market, a 118 year-old Portuguese church in Sikka village, Koka Beach, and Magepanda Mangrove Forest. The film was screened in film festivals in Busan, Tokyo, and Singapore.

Conclusion

Tiga Dara was carefully chosen to be restored with a long and costly process precisely because it has significant cultural importance relating to the 1950s and its messages still resonate into the millennial era. The film was a trendsetter for 1950s popular lifestyle and its discourses (gender issues, patriarchal culture, etc) seem to be timeless, remaining relevant today.

Moreover, its legacy of challenging society continues. Nia Dinata—a well-known feminist filmmaker who consistently produces films on gender and women’s rights—captures, interprets and translates the classical film for the context of 2016 in Three Sassy Girls.

Both films share similar ideas and spirit. Both films are significant for Indonesia’s context and for other nations and cultures which have similar problems and concerns.

Penulis: Ekky Imanjaya, Dosen Prodi Film Binus University.

Artikel ini sudah dimuat di Taiwan Studies Nusantara 2017.

Comments :